Saving New York

The story of the first century of firefighting in New York.

By Bruce Twickler

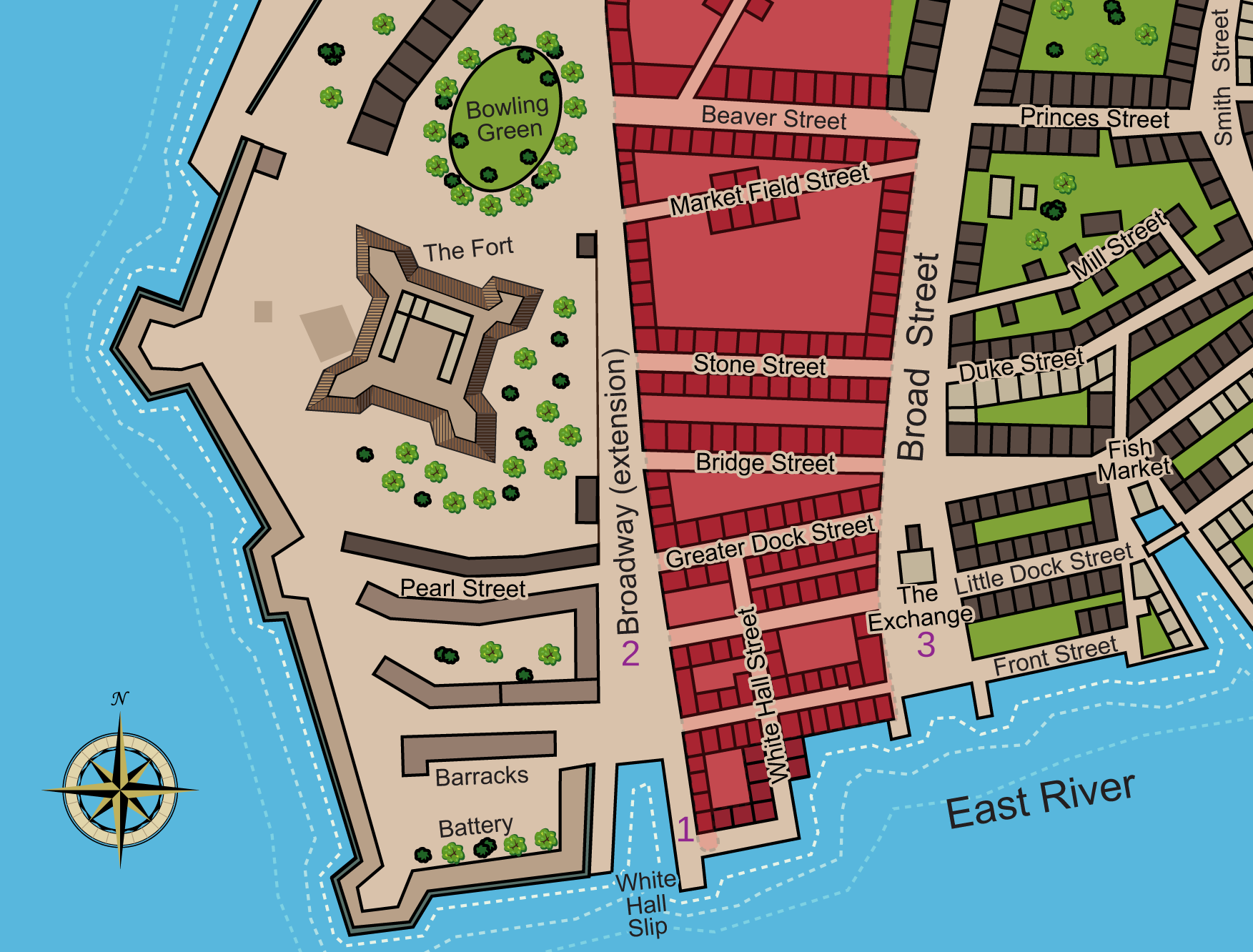

Shortly after midnight on September 21, 1776 several fires erupted in lower Manhattan. By daybreak they had consumed five hundred buildings. The timing of the fires was suspicious. British troops had been in the city for only a few days after forcing George Washington's army north. As the weight of evidence would eventually show, the fires were not accidental. They were pre-meditated if not planned, deliberate if not organized, designed to disorient if not devastate.

Washington followed the explicit orders from Congress to leave the city undamaged. In this Revolution, however, what the elite Congressional leaders directed were only rough guidelines for even rougher revolutionaries, like the Sons of Liberty, who had been burning Loyalist political pamphlets for years. When a few bonfires did not stop the flow of pro-British opinion, the Sons, unsympathetic to the notions of a free press, burned their buildings and destroyed their machines. With just a few thousand people still left in the city, mostly Loyalists, perhaps a few Sons and other 'good honest' fellows, as Washington fashioned it, "...had done more for us than we were disposed to do for ourselves."

However, one patriot, Jacobus Stoutenburgh, New York's Fire Chief, with Washington north of the city, might have had viewed the destruction of a large part of his hometown with less enthusiasm. He understood no doubt that depriving the British of a base of operations in New York was strategically useful for the Patriot cause. But he and his fellow firefighters, risking life and limb for forty years, had fought to protect that city from fire. More recently, they were the thin leather line that limited the havoc wreaked by the Sons of Liberty.

John B. Dash, one of Stoutenburgh's assistant engineers, a Loyalist, stayed in the city and fought fires, maybe not for the king, but for his own family and neighbors. Commissioned by the new British military governor, Dash and a few dozen firefighters took charge of the engines and formed the nucleus of the fire department in the city during the revolution. Like Stoutenburgh, Dash came up through the ranks. In addition to their abilities as leaders, both could work metal with precision. Stoutenburgh was a gunsmith; Dash, a tin smith - valuable skillsets in the repair and maintenance of fire engines.

What would happen to Stoutenburgh and Dash and the other firemen who had to make life-altering decisions when the shooting started? Their fate depended upon how the winning side, the Patriots, reconciled and reincorporated the Loyalist opposition, if they did. Before the war, Loyalists were not gently handled. In many ways what happened to the FDNY after the war is as surprising as what happened before and during the war.

Saving New York tells the fascinating story of how the heroic people of New York fought fires, saved lives, and protected their homes and livelihoods during the city's first hundred years. The sweeping narrative follows New York from its Dutch roots, the rapid all-colonist response of the bucket brigade, to the introduction of fire engines and the formation of the first group of dedicated volunteers "which Persons shall be Called the Firemen of the City of New York".

What made the colonial FDNY different from other periods was that it developed in the midst of wars with shooting and killing and looting and burning. In New York that included tribal raids, slave revolts, political rebellions, a few world wars, and a national revolution that was also a civil war. Colonists were compelled to develop firefighting and fight fires during and between these conflicts from the seventeenth century to and through the American Revolution. It was in the Dutch settlement of New Amsterdam in 1664, a few months before a major war with England, that Peter Stuyvesant as the leader of the colony would make his most important fire-prevention decision.